Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS)

Guidance for primary care clinicians diagnosing and managing children with POTS

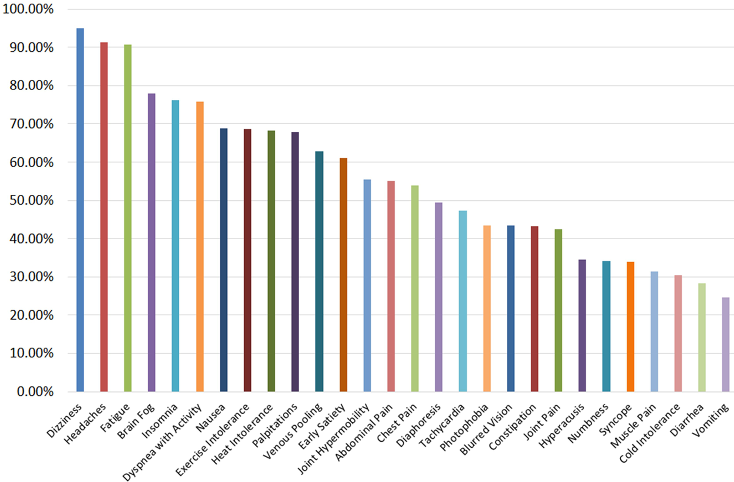

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is a form of autonomic dysfunction with orthostatic intolerance that affects up to 1% of adolescents with chronic fatigue, dizziness, and, often, gastrointestinal discomfort or other forms of chronic pain. The prevalence of POTS has increased after COVID-19 with 2%-14% of COVID-19 survivors developing POTS and 9%-61% experiencing POTS-like symptoms. While evaluating tired, dizzy, uncomfortable adolescents, consider the diagnosis of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome and/or orthostatic intolerance and identify any relevant comorbidities. POTS is a real condition, even if it is a functional disorder with normal laboratory testing and imaging results. Most patients can fully recover and return to normal life activities with treatment.

POTS can be especially challenging for young athletes used to strenuous physical activity. Managing expectations in this particular population can go a long way in treatment and recovery.

Other Names

- Autonomic disorder or autonomic dysfunction (over-arching group of conditions of which POTS is a subset)

- Dysautonomia (same as autonomic dysfunction)

- Disorders of gut-brain interaction

- Orthostatic intolerance (broad group of problems characterized by bothersome symptoms when upright that improves when lying down; POTS is the form that is chronic and associated with excessive postural tachycardia)

- Postural tachycardia syndrome (preferred in Great Britain and abbreviated “PoTS”)

Key Points

Importance of diagnosis

Patients with chronic functional disability and a variety of

symptoms often seek lots of subspecialty care. With normal results of tests,

patients tend to keep seeking new doctors and new tests. It is vitally important

that an informed care provider coordinates the evaluation and management. With

an accurate diagnosis of POTS and appropriate treatment, unnecessary

consultation and "doctor shopping" can be avoided, and the focus on functional

restoration maintained.

Diagnosis criteria

The diagnosis of POTS is based on clinical history (>3 months of

daily intolerance of upright position) coupled with postural tachycardia (>40

beats per minute increase for patients 12-19 years and >30 beats per minute

increase for patients over 19 years) within 10 minutes of upright posture. See

Diagnosis below for specific criteria. Acute and intermittent symptoms do not

qualify for the diagnosis. Similar symptoms without excessive postural

tachycardia indicate orthostatic intolerance but not POTS. The treatment would

be identical to the treatment of POTS, except that medications are not needed

for orthostatic intolerance when there is no excessive postural tachycardia.

Please see Diagnosis section for detailed criteria.

Management of POTS symptoms

Advise patients to drink so much that their urine looks clear,

like water. Eat as much salt as tolerated; some patients prefer salt

tablets/capsules. Get aerobic exercise daily (working up to 30 minutes in a

single daily session). Get enough sleep every night and do not take naps. If

this is not possible, limit naps to once a day and no longer than 30 minutes -

avoid napping after 2 pm. Get help from a good psychologist and consider

medication, too. Please see Treatment and Management Section for more

information.

Importance of healthy lifestyle

Patients with POTS are further compromised when they get behind on

exercise, regular meals, sleep, and other healthy habits that help with stress

management and weight gain. They must keep their bodies in balance. With POTS,

maintaining academic and extra-curricular success (or even participation) is

difficult. Loving parents tend to do whatever they can to help the patient

succeed. However, individuals typically link 2 activities with their recovery –

staying in school and exercising regularly, the very activities that are most

challenging with POTS. A clear diagnosis and treatment plan help patients and

families support activity and recovery rather than inactivity and illness.

Parents need to facilitate normal activities rather than helping the patient to

stay comfortable with increasing debilitation.

Physical therapy

Working with a physical therapist who is knowledgeable in POTS can

be very beneficial. Also, adjusting expectations in athletes is important so

they do not set themselves up to fail by having high standards for physical

activity. If there is joint hypermobility, work with a physical therapist

familiar with hypermobility to teach patients how to strengthen and protect

their joints. Please see the Exercise Section below to find more details on an

Exercise Program for patients with POTS.

Importance of healthy nutrition

Iron deficiency and vitamin D deficiencies can worsen POTS

symptoms. A balanced diet and taking a daily multivitamin can be helpful.

Evaluating for nutritional deficiencies can help guide management if there are

concerns about poor diet. If iron deficiency is suspected, an actual treatment

dose would be indicated (daily multivitamins might not have enough iron to treat

iron deficiency).

Infections and POTS

Patients with POTS tend to get sicker with common illnesses than

others. Patients with POTS feel terrible in just about every way with just about

any symptom. It is vitally important that they adhere to and even exaggerate

their baseline fluid/salt intake and exercise/activity plan when they are

ill.

Failure to improve

Patients need to keep going forward, 1 little step at a time.

Failure to improve only rarely relates to medication. Here are things to

emphasize:

- Become more aggressive about increasing fluid and salt intake.

- Focus on daily aerobic exercise. If the person is too tired to exercise, find the amount of upright exercise the patient can do – even if just 2 minutes of light walking. Make the exercise intense enough so the patient breathes a bit faster than normal. Then, increase the duration of that daily exercise by 1-2 minutes every 5 days. Gradually, exercise tolerance will increase. Keep going until the patient can continue with 30 minutes of aerobic exercise daily.

- Participating in cognitive behavioral therapy is very important.

Family and friends supporting the recovery of normal function (as opposed to comfort with disability) is vital.

Practice Guidelines

Mostly because of a lack of comparative studies of treatment options, there are no official Practice Guidelines for POTS. Below is a summary of what is known so far about pediatric POTS:

Boris JR, Moak JP.

Pediatric Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome: Where We Stand.

Pediatrics.

2022;150(1).

PubMed abstract / Full Text

See Helpful Articles in the Resources section for supportive literature.

Diagnosis

- Sustained heart rate increase of ≥ 30 beats/min (or ≥ 40 beats/min if patient is 12–19 yr within 10 minutes of upright posture.

- Absence of significant orthostatic hypotension (blood pressure drop ≥ 20/10 mm Hg).

- Very frequent symptoms of orthostatic intolerance that are worse while upright, with rapid improvement upon return to a supine position. Symptoms vary among individuals but often include lightheadedness, palpitations, tremulousness, generalized weakness, blurred vision, and fatigue.

- Symptom duration ≥ 3 months.

- Absence of other conditions that could explain sinus tachycardia on standing

- Acute hypovolemia (from dehydration or blood loss)

- Anemia

- Orthostatic hypotension

- Endocrinopathy

- Adrenal insufficiency

- Carcinoid tumor

- Hyperthyroidism

- Pheochromocytoma

- Adverse effects from medication or polypharmacy.

- Panic attacks and severe anxiety

- Prolonged or sustained bed rest

- Recreational drug effects

History

- What are your biggest concerns?

- When do you remember being completely healthy?

- What was the first thing that affected you? Any inciting event?

- Any aggravating/relieving factors?

- What have you tried so far? What has worked?

- What top 3 things would you like to be doing that you can't do right now?

- How long can you stand, exercise?

- Does heat bother you?

- How do you feel after large meals?

- Do you sweat like others?

- Any changes to bowel movements? Any trouble digesting food?

- Any changes to sexual life/function?

- Any urinary concerns?

Family History

Presentations

Patients have upright dizziness and feel better lying down. Sometimes, they also have other upright symptoms (headache, heaviness, fatigue, cloudy thinking) partially abated by lying down. Patients can experience blurred vision when dizzy. Sometimes, these patients can be pre-syncopal or syncopal.

Almost all POTS patients have had bothersome fatigue for at least 3 months.

Orthostatic hypotension sometimes develops after postural tachycardia when upright. If the systolic blood pressure drops more than 20 mm Hg and/or the diastolic pressure drops >10 mmHg within the first 3 min of upright position, prior to an increase in heart rate, the problem is orthostatic hypotension rather than POTS. One way or the other, patients with POTS sometimes faint.

Most POTS patients have at least some gastrointestinal distress, like irritable bowel syndrome and nausea (functional gastrointestinal disorder). Of course, before assuming that POTS is the cause, celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease should be considered.

Many patients with POTS have irregular temperature regulation, such as “wilting” outside on hot days, requiring different numbers of layers of clothes than peers, or sensing low-grade fevers.

Many POTS patients feel like they cannot think clearly or remember things. It is unclear whether this relates to altered cerebral blood flow or altered chemical activation of brain cells. However, cognitive testing does not usually reveal measurable deficits.

Diagnostic Criteria and Classifications

Genetics & Inheritance

Screening & Diagnostic Testing

Genetics & Inheritance

Prevalence

Differential Diagnosis

Co-Occurring Conditions

- Iron deficiency: Nearly ½ of patients with POTS have ferritin levels <20 ng/dL and benefit some from iron supplementation.

- Vitamin D deficiency: About ⅓ of POTS patients have 25-OH-vitamin D levels <20 ng/dL and benefit to some degree from vitamin D supplementation.

- Anxiety and depression: Approximately ⅓ of patients with POTS have significant anxiety and/or depression, some of which preceded the onset of POTS symptoms. Similar neurotransmitters are involved in the regulation of both the autonomic nervous system and mood, which may be a factor. Chronic debilitation due to POTS could also trigger depression.

- Headache and other forms of chronic pain: Seen in the majority of those with POTS

- Motion sickness: Also common in POTS

Prognosis

There are limited data about the outcomes of adolescent-onset POTS. A study including adolescents and adults found that approximately 37% no longer had POTS 1 year after starting treatment.[Kimpinski: 2012] A study of adolescents surveyed about 1½ years after starting treatment found that most were significantly improved, especially those treated with beta-blockers. [Lai: 2009] A longer (average 5 years) follow-up survey of adolescents with POTS demonstrated that symptoms of POTS were resolved or markedly reduced in about 86% of respondents. [Bhatia: 2016] Even a vast majority of adolescents with POTS and/or debilitating chronic pain can return to normal activities within months of completing an intensive recovery program. [Bruce: 2017] While not all adolescents with POTS fully recover, optimism for a good recovery for most affected patients is warranted.

Treatment & Management

Instruct patients to increase fluid and salt intake, exercise daily, get adequate sleep, and engage in cognitive behavioral therapy techniques. Prescription medications are most useful when the patient fully engages in non-pharmacologic treatment modalities. [Lai: 2009]

In 1 study, nearly 90% recovered or greatly improved over a few years. However, some patients do not fully recover. [Bhatia: 2016] Management of individuals with POTS requires patience, persistence, and positivity.

Non-pharmacologic treatment (fluids, salt, exercise, compression garments, elevating the head of bed, therapy) may be sufficient and should be used for all patients.

Pharmacologic treatment (fludrocortisone, beta-blockers, antidepressants) may be very helpful for select patients. Most of those needing medications can discontinue them after 1-3 years. Helping the patient and the family understand the condition, implement and maintain needed lifestyle and dietary changes, and sustain optimism and goals for the future are key. For management of many patients with POTS, a physician familiar with the condition and a psychologist skilled in cognitive behavioral therapy are the only specialists needed. If the primary care provider or medical home physician is unfamiliar with POTS, a POTS-aware physician can help – be that a generalist, a neurologist, or a cardiologist. Some patients are more likely to continue daily exercise if they have a physical therapist or coach involved. Some institutions have multi-disciplinary teams for POTS so patients can see a POTS-aware physician, a psychologist, and a physical therapist on the same day. It prevents repeated hospital visits and bills and allows for care coordination.

Approach to

Treatment of POTS ( Figure 2 from Postural orthostatic

tachycardia syndrome: a clinical review

[Johnson: 2010]

Click image to access the abstract - article requires a subscription

to Pediatric Neurology.)

Table 2 from Pediatric

disorders of orthostatic intolerance

[Stewart: 2018]

Click image for free access to table.

- Fluids: Fluid intake goal- 3-4L per day- about 100-120 ounces

- Salt: Salt intake goal- 3-4 Grams sodium/day. Do not worry about the patient taking in too much salt unless diagnosed with hypertension. Most patients do not get enough salt, so optimizing that is very important.

- Compression garments are helpful, too, especially waist-high compression leggings. They help prevent pooling in the legs and abdomen. The goal is to achieve 20-30 mm Hg. Some brands that have carried compression wear from time to time are Under Armour, Second Skin, Old Navy, SPANK, Lululemon, CEP compression.com, Therafirm, and Bauerfeind.

-

Exercise: Adaptation to fatigue and other symptoms of POTS often

leads to deconditioning, which requires reconditioning exercise to

reverse. Find the amount of upright exercise the patient can do – even

if just 2 minutes of light walking. Make the exercise intense enough to

gradually increase tolerance, aiming for at least 30-60 minutes of

aerobic exercise every day. Sometimes, patients comply better with

exercise regimens if followed and guided by a physical therapist. The

POTS Exercise Program (CHOP) (

1.4 MB) is

a unique exercise training program by the Children's Hospital of

Philadelphia designed for patients with POTS patients that starts with

exercise in a recumbent position.

1.4 MB) is

a unique exercise training program by the Children's Hospital of

Philadelphia designed for patients with POTS patients that starts with

exercise in a recumbent position.

- Elevate the head of the bed to reduce nocturnal diuresis and POTS symptoms.

Mental Health / Behavior

Medication

- Limit beta-blockers if there is excessive resting bradycardia.

- Absent excessive postural tachycardia, medications may not be indicated for orthostatic intolerance.

- If the patient still has excessive postural tachycardia an hour after taking a beta-blocker dose, the dose could be increased.

- Beta-blockers can cause rare worsening of asthma, rare difficulty recognizing symptoms of hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes, and occasional increased fatigue (especially with propranolol). Midodrine can cause a “creepy-crawly” sensation of the scalp with too high or too rapidly increasing a dose.

- Caffeine can stall recovery.

- Antihistamines might slightly hinder recovery, so they should only be used if truly needed.

Click image for free access to table.)

Table 2 from Pediatric disorders of orthostatic intolerance [Stewart: 2018]

Click image for free access to table.

Neurology

Gastro-Intestinal & Bowel Function

Nutrition

Endocrine/Metabolism

Cardiology

Musculoskeletal

Maturation/Sexual/Reproductive

Sleep

Education & School

Complementary & Alternative Medicine

Services & Referrals

For management of many patients with POTS, a physician who is familiar with the condition and a psychologist skilled in cognitive behavioral therapy are the only specialists needed. If the primary care provider or medical home physician is not familiar with POTS, the involvement of a POTS-aware physician can help – be that a generalist, a neurologist, or a cardiologist.

When to refer a patient with POTS

- No improvement noted with non-pharmacologic measures

- If the primary care clinician is not comfortable prescribing medications for POTS, or the patient does not improve with first-line medications like beta-blockers, or after targeting specific issues like anxiety and depression with SSRIs

- If symptoms are worsening

- If there are associated comorbidities complicating diagnostic picture and management

The Center for Autonomic Dysfunction and Research is a multi-disciplinary clinic for patients with POTS and dysautonomia. The team involves POTS-aware physicians, psychologists, and physical therapists.

Additional specialists can be helpful in the diagnosis and management of various aspects of care or comorbid conditions:

Pediatric Cardiology

(see NV providers

[4])

May be helpful in evaluation and management if sufficiently

experienced with POTS and to rule out concerning cardiac causes of syncope and

palpitations, if associated, or for specific cardiac concerns.

Pediatric Neurology

(see NV providers

[5])

May be helpful in evaluation if sufficiently experienced with POTS.

Physical Therapy

(see NV providers

[9])

May be helpful in designing and monitoring response to a

reconditioning program and for evaluation and management of excessive pain. Some

patients are more likely to continue daily exercise if they have a physical

therapist or coach involved.

Behavioral Therapies

(see NV providers

[19])

Referral for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is likely appropriate

for all those diagnosed with POTS.

Individual Counseling

(see NV providers

[4])

Other mental health providers may be helpful for assessment and

treatment of depression and/or anxiety, or if no CBT providers are available.

Pediatric Integrative Medicine

(see NV providers

[0])

May be helpful to direct components of management, including

traditional and complementary modalities in a safe and evidence-based manner.

Pediatric Gastroenterology

(see NV providers

[5])

May be helpful in managing GI problems not responsive to primary care

measures.

ICD-10 Coding

G90. A is a billable/specific ICD-10-CM code that can be used to indicate a diagnosis for reimbursement purposes. ICD-10-CM G90. A is a new 2023 ICD-10-CM code that became effective on October 1, 2022.

Resources

Information & Support

Related Portal Content

For Professionals

Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (GARD)

Includes information about symptoms, inheritance, diagnosis, finding a specialist, related diseases, and support organizations;

Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome - Grand Rounds Lecture

One-hour video of a Grand Rounds lecture at Primary Children's Hospital by Phillip Fischer, MD (2014), includes patient accounts

of the condition.

Patient Education

POTS (Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome) (FAQ)

Answers to questions that families may have about

POTS.

Patient Education for POTS (Primary Children's Hospital) ( 239 KB)

239 KB)

Detailed recommendations for care of an adolescent with POTS or orthostatic intolerance.

Postural Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) (Mayo Clinic)

Five-minute video for patients and families of Phil Fischer, MD (author of this module) explaining POTS.

Tools

Table of Medications to Manage POTS

Medication, Dosing, Side Effects, and comments; from Stewart JM, Boris JR, Chelimsky G, Fischer PR, Fortunato JE, Grubb BP,

Heyer GL, Jarjour IT, Medow MS, Numan MT, Pianosi PT, Singer W, Tarbell S, Chelimsky TC. Pediatric disorders of orthostatic

intolerance.

Pediatrics. 2018;141

Services for Patients & Families in Nevada (NV)

| Service Categories | # of providers* in: | NV | NW | Other states (3) (show) | | NM | RI | UT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Therapies | 19 | 1 | 17 | 32 | 36 | |||

| Individual Counseling | 4 | 36 | 9 | |||||

| Pediatric Cardiology | 4 | 3 | 17 | 4 | ||||

| Pediatric Gastroenterology | 5 | 2 | 18 | 2 | ||||

| Pediatric Integrative Medicine | 1 | |||||||

| Pediatric Neurology | 5 | 5 | 18 | 8 | ||||

| Physical Therapy | 9 | 12 | 6 | 40 | ||||

For services not listed above, browse our Services categories or search our database.

* number of provider listings may vary by how states categorize services, whether providers are listed by organization or individual, how services are organized in the state, and other factors; Nationwide (NW) providers are generally limited to web-based services, provider locator services, and organizations that serve children from across the nation.

Studies

Clinical Studies of POTS (clincaltrials.gov)

Studies looking at better understanding, diagnosing, and treating this condition; from the National Library of Medicine.

Helpful Articles

Ormiston CK, Świątkiewicz I, Taub PR.

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome as a sequela of COVID-19.

Heart Rhythm.

2022;19(11):1880-9.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Raj SR, Fedorowski A, Sheldon RS.

Diagnosis and management of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.

CMAJ.

2022;194(10):E378-E385.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Rao P, Peritz DC, Systrom D, Lewine K, Cornwell WK 3rd, Hsu JJ.

Orthostatic and Exercise Intolerance in Recreational and Competitive Athletes With Long COVID.

JACC Case Rep.

2022;4(17):1119-1123.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Bourne KM, Sheldon RS, Hall J, Lloyd M, Kogut K, Sheikh N, Jorge J, Ng J, Exner DV, Tyberg JV, Raj SR.

Compression Garment Reduces Orthostatic Tachycardia and Symptoms in Patients With Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome.

J Am Coll Cardiol.

2021;77(3):285-296.

PubMed abstract

Cooper VL, Hainsworth R.

Head-up sleeping improves orthostatic tolerance in patients with syncope.

Clin Auton Res.

2008;18(6):318-24.

PubMed abstract

Tome J, Kamboj AK, Loftus CG.

Approach to Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction.

Mayo Clin Proc.

2023;98(3):458-467.

PubMed abstract

Authors & Reviewers

| Author: | Kirti Sivakoti, MD |

| Reviewer: | Phil Fischer, MD |

| 2023: update: Kirti Sivakoti, MDA |

| 2020: revision: Gisela G. Chelimsky, MDR |

| 2019: first version: Phil Fischer, MDA |

Page Bibliography

Bhatia R, Kizilbash SJ, Ahrens SP, Killian JM, Kimmes SA, Knoebel EE, Muppa P, Weaver AL, Fischer PR.

Outcomes of Adolescent-Onset Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome.

J Pediatr.

2016;173:149-53.

PubMed abstract

Over a few years, 86% or more of patients with adolescent-onset POTS report recovery or significant improvement.

Boris JR, Moak JP.

Pediatric Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome: Where We Stand.

Pediatrics.

2022;150(1).

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Bourne KM, Sheldon RS, Hall J, Lloyd M, Kogut K, Sheikh N, Jorge J, Ng J, Exner DV, Tyberg JV, Raj SR.

Compression Garment Reduces Orthostatic Tachycardia and Symptoms in Patients With Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome.

J Am Coll Cardiol.

2021;77(3):285-296.

PubMed abstract

Bruce BK, Weiss KE, Ale CM, Harrison TE, Fischer PR.

Development of an Interdisciplinary Pediatric Pain Rehabilitation Program: The First 1000 Consecutive Patients.

Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes.

2017;1(2):141-149.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Cooper VL, Hainsworth R.

Head-up sleeping improves orthostatic tolerance in patients with syncope.

Clin Auton Res.

2008;18(6):318-24.

PubMed abstract

Ghandour RM, Overpeck MD, Huang ZJ, Kogan MD, Scheidt PC.

Headache, stomachache, backache, and morning fatigue among adolescent girls in the United States: associations with behavioral,

sociodemographic, and environmental factors.

Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.

2004;158(8):797-803.

PubMed abstract

Johnson JN, Mack KJ, Kuntz NL, Brands CK, Porter CJ, Fischer PR.

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: a clinical review.

Pediatr Neurol.

2010;42(2):77-85.

PubMed abstract

Since this publication, the diagnostic criteria for adolescent POTS have been refined to include a postural tachycardia of

at least 40 beats per minute change (instead of 30, as for adults). The suggested non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment

strategies remain the same.

Kimpinski K, Figueroa JJ, Singer W, Sletten DM, Iodice V, Sandroni P, Fischer PR, Opfer-Gehrking TL, Gehrking JA, Low PA.

A prospective, 1-year follow-up study of postural tachycardia syndrome.

Mayo Clin Proc.

2012;87(8):746-52.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Lai CC, Fischer PR, Brands CK, Fisher JL, Porter CB, Driscoll SW, Graner KK.

Outcomes in adolescents with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome treated with midodrine and beta-blockers.

Pacing Clin Electrophysiol.

2009;32(2):234-8.

PubMed abstract

Even over the months of initial treatment, most patients receiving a beta-blocker improve and credit the medication with their

improvement.

Ojha A, Chelimsky TC, Chelimsky G.

Comorbidities in pediatric patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.

J Pediatr.

2011;158(1):20-3.

PubMed abstract

Ormiston CK, Świątkiewicz I, Taub PR.

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome as a sequela of COVID-19.

Heart Rhythm.

2022;19(11):1880-9.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Raj SR, Fedorowski A, Sheldon RS.

Diagnosis and management of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.

CMAJ.

2022;194(10):E378-E385.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Rao P, Peritz DC, Systrom D, Lewine K, Cornwell WK 3rd, Hsu JJ.

Orthostatic and Exercise Intolerance in Recreational and Competitive Athletes With Long COVID.

JACC Case Rep.

2022;4(17):1119-1123.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Rimes KA, Goodman R, Hotopf M, Wessely S, Meltzer H, Chalder T.

Incidence, prognosis, and risk factors for fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome in adolescents: a prospective community study.

Pediatrics.

2007;119(3):e603-9.

PubMed abstract

Shaw BH, Stiles LE, Bourne K, Green EA, Shibao CA, Okamoto LE, Garland EM, Gamboa A, Diedrich A, Raj V, Sheldon RS, Biaggioni

I, Robertson D, Raj SR.

The face of postural tachycardia syndrome - insights from a large cross-sectional online community-based survey.

J Intern Med.

2019;286(4):438-448.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Silverman MN, Heim CM, Nater UM, Marques AH, Sternberg EM.

Neuroendocrine and immune contributors to fatigue.

PM R.

2010;2(5):338-46.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Stewart JM, Boris JR, Chelimsky G, Fischer PR, Fortunato JE, Grubb BP, Heyer GL, Jarjour IT, Medow MS, Numan MT, Pianosi PT,

Singer W, Tarbell S, Chelimsky TC.

Pediatric disorders of orthostatic intolerance.

Pediatrics.

2018;141(1).

PubMed abstract / Full Text

This paper reviews standard management of adolescents with POTS and also mentions non-standard treatments that only have anecdotal

support of efficacy.

Tarbell SE, Olufs EL, Fischer PR, Chelimsky G, Numan MT, Medow M, Abdallah H, Ahrens S, Boris JR, Butler IJ, Chelimsky TC,

Coleby C, Fortunato JE, Gavin R, Gilden J, Gonik R, Klaas K, Marsillio L, Marriott E, Pace LA, Pianosi P, Simpson P, Stewart

J, Van Waning N, Weese-Mayer DE.

Assessment of comorbid symptoms in pediatric autonomic dysfunction.

Clin Auton Res.

2023.

PubMed abstract

ter Wolbeek M, van Doornen LJ, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ.

Severe fatigue in adolescents: a common phenomenon?.

Pediatrics.

2006;117(6):e1078-86.

PubMed abstract

Tome J, Kamboj AK, Loftus CG.

Approach to Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction.

Mayo Clin Proc.

2023;98(3):458-467.

PubMed abstract

Get More Help in Nevada

Get More Help in Nevada